Swimming the Questions

Further and "final" reflections from Brent Raycroft on Anne Carson's Wrong Norma and Emily Wilson's "Fox and Hedgehog."

By ‘politics in Wrong Norma’ I mean the kind of politics that Emily Wilson in “Fox and Hedgehog” finds lacking in Anne Carson’s first book:

She has much to say about the intricacies of “Sappho’s mind,” but nothing about her complicated status as an aristocrat in an era of political turbulence and revolution….

Wilson later observes that the author has broadened her horizons since Eros the Bittersweet. (It has been almost 35 years….)

…in Wrong Norma, more than in her earlier work, Carson is also interested in the connections that join the social fabric together and the places where it frays.

True enough, but Wilson deliberately minimizes. Reading “1=1”, the first piece in the book, she treats the speaker’s cognitive dissonance—between her aesthetic concerns as a solitary swimmer and the plight of refugees—as a catching up to familiar truisms, not a beginning.

Where the crafted persona of the younger Carson was often too much inside her own head to worry about politics, this late-era Carson knows that there is a price for everything, including her own devotion to beauty and the self.

Carson does bring up “price” in “1=1.”

Across the level ocean of her mind come floating certain refugees in a makeshift plastic boat…stacked in layers and dropping over the sides.

Her protagonist asks (without asking):

What is the price of desolation and who pays. Some questions don’t warrant a question mark.

Does “1=1” describe a simple circuit from complacent insularity outward to pity for drowning migrants and back to a wiser egotism? Not quite.

Let’s compare foxes. The speaker here is not—or perhaps is no longer—Anne Carson. There’s no direct mention of her being a writer or visual artist. The speaker’s neighbor (even more clearly not Anne Carson) makes chalk drawings on the sidewalk. At the end of his day he shows her a “fox, swimming in a blue-green jellylike lucidity of its own…escaping all possible explanations” and “stroking splashlessly forward.” Through his completed artwork he “is once again absolved.”

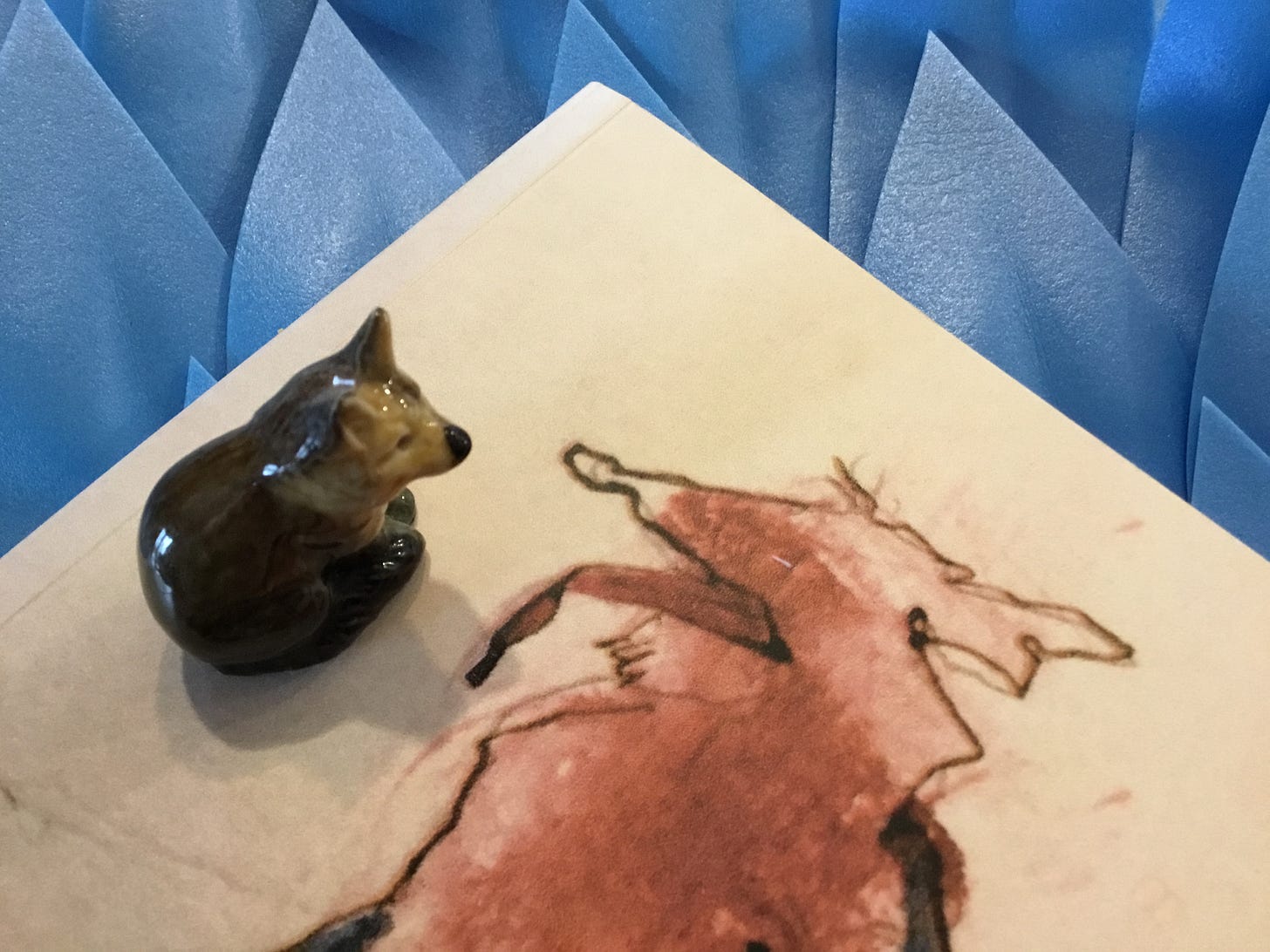

But the fox on the cover of Wrong Norma—Carson’s fox—is a different fox. Hers is not swimming, not moving forward, not even resolved as an image. Exhausted? Manic? Washed up on a sandy shore?

The speaker in “1=1” is not absolved. The swimming fox provides her with only a moment of internal quiet: “Ethics minimal. Try to swim without thinking how it looks.”

Granted, she admits she is “one of the most selfish people she has ever known….It is an aspect of personality hard to change.” Wilson takes this as a static confession by the author, not a moment for a character.

Wilson’s essay proceeds immediately from the first to the second-to-last piece in Wrong Norma, “Todtnauberg,” a collage “comic” with minimal text depicting the poet Paul Celan’s visit with the philosopher Martin Heidegger.

Both of these “bookend” readings involve interventions via questions. In “1=1” Carson rejects the question mark because she is pointing directly to “who pays”—the suffering, drowning migrants. Wilson chooses to interpolate instead what she concludes is paid for: Anne Carson’s “devotion to beauty and the self.”

Reading “Todtnauberg” Wilson asks the questions, and presumes to bundle them en masse into Carson’s text:

Why did Celan visit Heidegger? What did the visit mean to him? What did they say to each other? Whose fault was his death, and so many other deaths? What do Hellenophilia or poetry have to do with the Holocaust? So much is, as Carson notes, “unknown.”

What Carson actually deems “unknown” is only one of these questions. She even gives us facts enough to answer some of the others on the first page of “Todtneuberg”:

In the same presumptuous way that Wilson provides Carson with the moral of the story in “1=1,” she would have Carson concede in “Todnauberg” to a much greater range of “unknowns” than the text warrants.

The most surprising of Wilson’s would-be “unknowns” is the last. “What do Hellenophilia or poetry have to do with the Holocaust?” This is really two questions, but the answer to both is: “a lot.” There are whole books on these topics.

The word “Hellenophilia” is modern, dating from the 1960s, and while it is often used neutrally for a benign love of ancient Greek culture, “Philhellenism” is the more common word for that, dating back to Roman times. The newer coinage is entangled with an excessive, exclusive focus on ancient Greece. If “Hellenophilia” sounds like a perversion, that’s because, in a way, it is. Not sexual, but geo-political and geo-cultural.

A simple but significant inversion. Similarly “Philosophy” has a familiar, respectable sound, but “Sophophilia” not so much. While the latter sometimes gets used as a synonym, it also appears on the DSM list of paraphilias, or “atypical” sexual interests. (I should confess that I myself and most of my friends are a bit atypical in this way.)

After praising some of the shortest works in Wrong Norma, Wilson suggests “Many of the longer pieces…are less successful….” It’s just her opinion, but it’s an opinion that excludes a large portion of the book—and its clearest politics.

The longest work in Wrong Norma is “Lecture on the History of Skywriting.” Among many other things, it includes a lengthy section considering the sky as a medium of warfare, from spears to missiles. That section is presented in both English and Arabic text.

“Skywriting” is a downer, but often funny, and undeniably political. The Sky declares “I didn’t, I don’t, expect you creeping creatures that creep upon the earth to stop wanting warfare anytime soon.” (Note she doesn’t say “ever.”)

“Skywriting” has much that defies Wilson’s pronouncement that “other people are still not really [Carson’s] thing.” Anti-war sentiments form the base, topped off with Carson’s clear axiom toward the end: “No one can tell a story without believing in the reality of others.”

“Thret,” another long work, Wilson dismisses as “meandering,” an experiment that “allow[s] Carson to play with plot.” But “Thret” is where Carson takes on school shootings, activism, and actionism. Using a surreal crime-novel style she explores the vicarious trauma that many of us feel when faced with atrocities in the news. Or in our town.

“Fate, Federal Court, Moon” goes unmentioned. It draws on Carson’s own political activism. With the human rights group Reprieve she supported a legal claim through the courts. The complainant was seeking accountability from the US government for an Obama-era drone-strike that killed members of his family in Yemen.

Who pays. Some questions don’t warrant a question mark.